In honor of Black History Month, I have dedicated this month's post to honor 10 more than notable African Americans. I purposefully avoided including entertainers, musicians, sports figures and those whose major contributions were in the civil rights area. I feel all of the above have been lauded to the point that there are very few left who have not become familiar with them and their stories. Rather I have chosen people who acquired their money, fame and place in history due solely to their pursuit of knowledge and a better life not only for themselves but for their fellow members of the human race.

I'm going to begin with a man who was not born in America. He was Canadian by birth but his family moved to the US when he was a child. His name was Elijah McCoy.

Elijah's parents (George and Mildred) were fugitive slaves from Kentucky who fled to Canada. They produced 12 children 10 of which were born in Canada. According to census records, George moved his growing family to Ypsilanti, Michigan in 1859-1860.

When Elijah was 15 he received an apprenticeship to Scotland. After some years he was certified as a mechanical engineer. While he was studying in Scotland, his father found work farming.

After spending several years farming and saving his money, George McCoy used his vast knowledge in tobacco to establish a successful Tobacco and Cigar company in Ypsilanti.

When Elijah returned to Michigan, he began his life's work of invention. While his list of inventions is long, he is perhaps most known for his invention of what was considered the perfect oil drip cup. It was so preferred that when competitors tried to copy Elijah's product, customers were outraged.

They would ask for the "real McCoy". Thus a slang term was born that has lasted right up til now.

Sarah Breedlove, who later would come to be known as Madam C. J. Walker, was born on December 23, 1867 on the same Delta, Louisiana plantation where her parents, Owen and Minerva Anderson Breedlove, had been enslaved before the end of the Civil War. This child of sharecroppers transformed herself from an uneducated farm laborer and laundress into one of the twentieth century’s most successful, self-made women entrepreneurs.

Orphaned at age seven, she often said, “I got my start by giving myself a start.” She and her older sister, Louvenia, survived by working in the cotton fields of Delta and nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi. At 14, she married Moses McWilliams to escape abuse from her cruel brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.

Her only daughter, Lelia (later known as A’Lelia Walker) was born on June 6, 1885. When her husband died two years later, she moved to St. Louis to join her four brothers who had established themselves as barbers. Working for as little as $1.50 a day, she managed to save enough money to educate her daughter in the city’s public schools. Friendships with other black women who were members of St. Paul A.M.E. Church and the National Association of Colored Women exposed her to a new way of viewing the world.

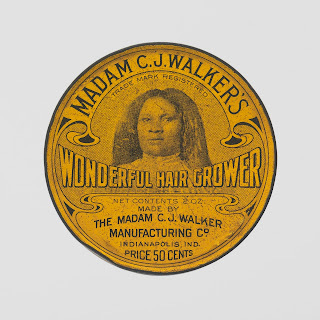

During the 1890s, Sarah began to suffer from a scalp ailment that caused her to lose most of her hair. She consulted her brothers for advice and also experimented with many homemade remedies and store-bought products, including those made by Annie Malone, another black woman entrepreneur. In 1905 Sarah moved to Denver as a sales agent for Malone, then married her third husband, Charles Joseph Walker, a St. Louis newspaperman. After changing her name to “Madam” C. J. Walker, she founded her own business and began selling Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, a scalp conditioning and healing formula, which she claimed had been revealed to her in a dream. Madam Walker, by the way, did NOT invent the straightening comb or chemical perms, though many people incorrectly believe that to be true.

To promote her products, the new “Madam C.J. Walker” traveled for a year and a half on a dizzying crusade throughout the heavily black South and Southeast, selling her products door to door, demonstrating her scalp treatments in churches and lodges, and devising sales and marketing strategies. In 1908, she temporarily moved her base to Pittsburgh where she opened Lelia College to train Walker “hair culturists.”

As her business continued to grow, Walker organized her agents into local and state clubs. Her Madam C. J. Walker Hair Culturists Union of America convention in Philadelphia in 1917 must have been one of the first national meetings of businesswomen in the country. Walker used the gathering not only to reward her agents for their business success, but to encourage their political activism as well. “This is the greatest country under the sun,” she told them. “But we must not let our love of country, our patriotic loyalty cause us to abate one whit in our protest against wrong and injustice. We should protest until the American sense of justice is so aroused that such affairs as the East St. Louis riot be forever impossible.”

By the time she died at her estate, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, she had helped create the role of the 20th Century, self-made American businesswoman; established herself as a pioneer of the modern black hair-care and cosmetics industry; and set standards in the African-American community for corporate and community giving.

Tenacity and perseverance, faith in herself and in God, quality products and “honest business dealings” were the elements and strategies she prescribed for aspiring entrepreneurs who requested the secret to her rags-to-riches ascent. “There is no royal flower-strewn path to success,” she once commented. “And if there is, I have not found it for if I have accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard.”

I'm going to begin with a man who was not born in America. He was Canadian by birth but his family moved to the US when he was a child. His name was Elijah McCoy.

Elijah's parents (George and Mildred) were fugitive slaves from Kentucky who fled to Canada. They produced 12 children 10 of which were born in Canada. According to census records, George moved his growing family to Ypsilanti, Michigan in 1859-1860.

When Elijah was 15 he received an apprenticeship to Scotland. After some years he was certified as a mechanical engineer. While he was studying in Scotland, his father found work farming.

After spending several years farming and saving his money, George McCoy used his vast knowledge in tobacco to establish a successful Tobacco and Cigar company in Ypsilanti.

When Elijah returned to Michigan, he began his life's work of invention. While his list of inventions is long, he is perhaps most known for his invention of what was considered the perfect oil drip cup. It was so preferred that when competitors tried to copy Elijah's product, customers were outraged.

They would ask for the "real McCoy". Thus a slang term was born that has lasted right up til now.

John Merrick

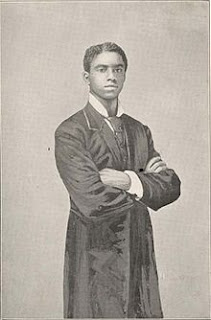

John Merrick aged 20

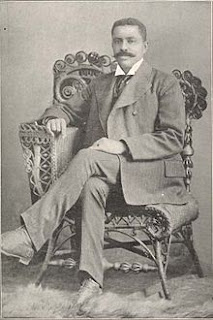

John Merrick aged 35

John Merrick's childhood home in upper right corner and his home at the time of his death

John Merrick's life was indeed a rags to riches story. Born into slavery in Clinton, North Carolina in 1859, Merrick relied on his enormous intelligence, social savvy, entrepreneurial spirit, inner drive and ambition to achieve great personal wealth throughout his lifetime.

Following his emancipation, John Merrick learned how to read and write in a reconstructionist school. As a young child, Merrick was going to school and working in order to support his parents and siblings. He worked as a brick mason among other odd jobs. Once he learned to read and write, Merrick began to study to become a barber. His barbershop was the first of many successful businesses.

Merrick’s success did not stop there. His newly gained experience from his barbershop ventures propelled him further into the business world by laying the groundwork for the creation of many other prosperous companies. These successive business undertakings brought Merrick immense wealth and financial security.

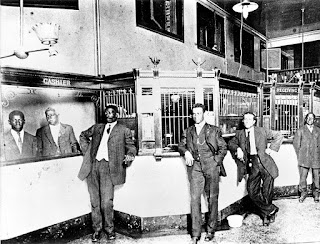

His journey into the world of entrepreneurship was uncharacteristic of and therefore extraordinary for a black man of his time, yet the city of Durham did not possess the “white aristocracy” that could be found in “older cities like New Orleans”. John Merrick’s various business endeavors included his participation in the creation of the well-known North Carolina Mutual Company, the Merrick-Moore-Spaulding Real Estate Company, the Mechanics and Farmers Bank, and the Bull City Drug Company.

R. Andrew McCants commented that “it is only natural that a man who has been personally very successful in the conduct of his own business,” which in Merrick’s case was his barbershops, “become a leader in community enterprises,” a feat he achieved with the establishment of his various companies.

Merrick’s most profitable and noteworthy undertaking was the creation of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. He cultivated his relationships with Durham’s influential white families that had developed from his selfless personality and reliable business practices.

Being the personal barber of Washington Duke, the two became such close companions that Duke was more than willing to loan Merrick the money to cover the start up costs of his new company. Together with Dr. Aaron Moore and Charles C. Spaulding, Merrick helped increase the wealth of the “oldest and largest African American life insurance company in the United States”.

North Carolina Mutual was hugely successful—the company sold $4,986,344.40 of insurance and conducted business in many southern states across America. The enterprise grew into the “world’s largest Negro business” of the time, making Merrick one of the most successful black men of the time.

Largely thanks to John Merrick, A new black middle class emerged in Durham. The city’s black elite had the chance to explore the real estate, insurance, banking, and pharmaceutical industries instead of accepting the strenuous, run-of-the-mill jobs that

whites did not want.

Durham’s blacks finally had opportunities to explore employment options that would not have been available to them had Merrick not started his many businesses. Merrick’s powerful status also served as an example to Durham’s black community that they could rise to prominence and achieve entrepreneurial success no matter their skin tone.

His financial success and rising influence gave them hope. If John Merrick, a black once bound to slavery, could start his own business and ultimately build an empire, why couldn’t they? The Journal of Negro History notes that, because blacks now had opportunities to be employed by new businesses or to create their own businesses, they “emerged into a new social, economic, and intellectual order”.

Shelley Stewart

Spend a few minutes with Shelley Stewart, and you will come away with one thought. At 82 years young, the renowned advertising exec may be the most positive person on the planet.

“We have the privilege of working every day with a man who leads us, who energizes the room when he walks in,” said Bill Todd, the president of o2ideas, which Stewart founded 50 years ago. “But even when he’s not here we feel his presence because he’s created this spirit of togetherness, a sense of ‘I really care about you.’”

That’s the Shelley Stewart the Birmingham, Alabama business community knows, as do clients across the U.S. and the world – from Honda to Verizon to Buffalo Rock.

The Shelley Stewart they know is a man who sees the good in everyone.

But once you really know Shelley Stewart, his outlook and contributions are even more remarkable.

Born in 1934, reared in the African-American neighborhood of Rosedale, south of downtown Birmingham, Stewart grew up in an era of segregation and Jim Crow laws with three brothers. Still, life was good until everything changed in a moment’s time.

Tragedy

At age 5, Stewart was sitting on the front porch with his older sibling, Bubba, when his father raced past them and hurried into the house. Suddenly, there was a commotion.

“Mama was running up the hallway trying to get away from him, and he had an axe,” Stewart remembered. “She hollered, ‘Don’t take me away from my children!’”

The pleas were to no avail. At an age when children should be most innocent, Stewart and his 7-year-old brother witnessed their mother’s brutal death, at the hands of their own father.

Before his 8th birthday, Bubba left for parts unknown. Two years later, Shelley Stewart did the same. He survived for months finding temporary shelters and scavenging for food scraps tossed out behind grocery stores and restaurants.

Once outside a restaurant, an older African-American worker caught him scrounging for food. Instead of feeling empathy, the man chased the 7-year-old away with a swift kick and a flurry of curses. It was time to move on, further from the neighborhood that once offered peace and comfort.

It was getting late, when he noticed a barn in the distance.

“Something told me go inside that barn and sleep. I was tired and I was hungry, so I headed that way. But when I got to the breezeway I heard some voices. ‘Oh, God, they’re going to kill me.’”

Frightened, finding a place to hide, Stewart continued to listen. One voice had a familiar cadence.

“There was a voice I’d heard before,” Stewart continued. “I was hiding on one end, but I thought to myself, ‘that sounds like Bubba.’ Lo and behold, it was my brother, who had taken refuge in that barn two years before.”

The barn belonged to Stringfellow Stables, a local outfit that trained Tennessee Walking Horses. The owner, a white businessman with a successful lumber company, was named Earl Stringfellow. Two years earlier, he’d taken in Stewart’s brother, Bubba. Now, the Stringfellow family was willing to take in another orphaned youth.

Stability

For the first time in memory, Shelley Stewart had stability, and a place he could call home.

As life returned to normal, Stewart returned to school. Years later, he remembers his first grade teacher: Mamie Foster. He still recalls her words and deeds.

“One day she grabbed me and hugged me – I’d never been hugged before – and said, ‘If you learn to read, if you get a good education, you can be anything you want to be.’”

The words of Stewart’s teacher provided a guidepost. He learned to love reading, he got a solid education and went to work, as a young adult, as a popular Birmingham radio personality, having a huge following that included both the city’s black and white teens. He became known as Shelley The Playboy due to his smooth, on-air persona.

Civil Rights Movement

During the 1950s and ‘60s, Birmingham was about to explode. It was the epicenter of the human rights struggle referred to as the Civil Rights Movement, a focus of local, national and international attention. Amid political rancor and social upheaval, Stewart was the melodic, calming voice that came over the airwaves, the voice of reason amid chaos.

“He used the opportunity at the radio station and the radio market as a platform, as well as to talk about the value of an education, learning how to read, staying in school and make something of yourself,” remembered Perry Ward, a life-long friend who serves as the president of Lawson State Community College.

Stewart also took action. In the wake of the deadly bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, he used the airwaves to help conduct the famous children’s march. What started peacefully, with children leaving school to protest segregation in Alabama’s largest city, ended with Bull Connor ordering the use of fire hoses and police dogs on the children. The moment galvanized a nation, and brought Birmingham’s injustices to the attention of the world.

Bowed, but unbroken, Stewart continued with his message of positivity, of gains made through education. In 1967, he became a silent partner alongside a Jewish friend for a fledgling advertising agency – an unheard of move in the Deep South. Fifty years later, o2ideas remains a fixture in the business community.

Nourishment

Years have passed, but Shelley Stewart hasn’t changed much.

“This is a man who had every right to be bitter, yet somehow he chose early on to pursue a different path,” said Andrew Westmoreland, president of Samford University. “It’s that irrepressibly positive spirit about him that has compelled him forward. I just wish that all of us could have, in just a portion, the positive attitude he has. I’ve never heard him speak ill of another human.”

Think back to that time, years ago, where the only food to be had was what he could find behind a restaurant. To most it was refuse.

To Shelley Stewart, it was nourishment.

If he found bad bread, he’d pick it clean until he found edible parts. That lesson taught him to look at people the same way.

“If there’s a human being sitting there, I’d never throw the whole human being away,” Stewart said. “There’s some good in all of us. If there’s good, I’ll take it. And if there’s bad, I’m going to find the good part and turn the bad part good.”

This story originally appeared on regions.doingmoretoday.com

William Reuben Pettiford

William Reuben Pettiford (1847-1914) was an educator, banker, and Baptist minister who founded the Alabama Penny Savings Bank in Birmingham in 1890. The bank was the first financial institution owned and operated by blacks in the state. He served as the minister of the 16th Street Baptist Church from 1883 to 1893.

To say he was just a minister and banker would be a gross injustice not only to Mr. Pettiford, but to the legacy that he left not only in Birmingham, Alabama but across the nation.

In 1890 he founded the Alabama Penny Savings Bank, which played an important role in black economic development in Alabama and in the South during the 25 years it existed. Pettiford has been called the most significant institutional builder and leader in the African American community in Birmingham during the period in which he lived. In 1897 he was said to be next to Booker T. Washington as the man who has done the most in the South for blacks.

Dr. Cornelius Nathaniel Dorsette

Cornelius N. Dorsette (1852?-1897) is often identified as the first licensed or certified black physician in Alabama. He maintained a long-time practice in Montgomery, Montgomery County, where he spent the majority of his life. In addition to his successful medical practice, Dorsette owned an office building, operated a drug store, and established the first hospital for blacks in the state. He supported other black professionals in the city and was active in the Republican Party. Although he is often described as the first black physician in the state, he was one of several who practiced in the 1880s.

Dorsette's birthplace is usually identified as Eden, North Carolina, in Rockingham County; his birth year may have been 1851, 1852, or 1859. He was the first of six children of David, likely a farmer, and Lucinda Dorsette. He is often described as having been born in slavery. Dorsette attended primary school in Thomasville, Davidson County, and then entered the famed Hampton Institute, a Virginia college for freed slaves founded in 1868, where he was a classmate of Booker T. Washington, founder of what is now Tuskegee University. Dorsette graduated from Hampton in 1878.

A white trustee of the college, a Dr. Vosburgh, hired Dorsette to work as a driver and handyman at his home in Syracuse, New York. Vosburgh inspired Dorsette to seek a career in medicine and assisted with that goal. Dorsette studied Latin and then entered Syracuse University's medical school but was forced to drop out for health reasons. After he recovered, and with an offer of financial assistance from Vosburgh, Dorsette applied to the medical school at the University of the City of New York. He was turned down because of his race but was admitted to the University of Buffalo medical school and became the second black graduate there in 1882.

During the next two years, Dorsette worked in various medical positions in New York, including the poor house and insane asylum of Wayne County. He also had a general practice and worked in the psychiatric ward of the hospital in Lyons, New York. This working pace enabled him to repay Vosburgh by 1884.

In early 1883, Dorsette began efforts to locate elsewhere. He contacted his Hampton friend Booker T. Washington to get his advice; Washington, who had been named the first leader of the new Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers in 1881, urged Dorsette to relocate to Montgomery. In a February 28 letter, Washington assured his friend that such services were greatly in need in Alabama's capital city. Upon visiting Montgomery, Dorsette apparently liked his prospects enough to move to the city. He faced one major hurdle, however, in the state's medical certification process. Under the Alabama Medical Practice Act of 1877, candidates had to sit for a six-day examination by either a county board or the state board of medical examiners in Montgomery. All members of such boards were white male physicians, and Dorsette's performance was judged harshly by them but he passed and was licensed.

Dorsette quickly earned the respect of Montgomery's white medical leaders, but at first the African American citizens did not respond positively to his presence. Early black physicians faced suspicion because they were seldom as well-trained as their white counterparts, and African Americans who could afford medical care preferred to see white doctors. Dorsette overcame this attitude by his willingness to drive into the countryside to provide care and deliver babies.

He travelled to Tuskegee to serve as Washington's personal physician and offer care to faculty and students as well. He used his knowledge of vaccines to limit the scope of a smallpox epidemic in central Alabama. In the early 1880s, he was appointed to the school's Board of Trustees and served until his death. In 1891, he tutored Halle Tanner Dillon, a graduate of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania whom Washington had recruited to become the staff physician at Tuskegee. With Dorsette's help, she became both the first black woman to take the exam and the first woman to pass the test in the state.

Despite threats from some whites who resented his success, Dorsette remained in Montgomery. Within a few years, he had built a three-story structure on Dexter Avenue that housed his office, a drug store, and an auditorium on the top floor. He also provided space to other black physicians, as well as pharmacists, a dentist, and an attorney. Also located in the Dorsette Building was the office of Harvey Patterson, a newspaper editor who published the Montgomery Argus for the local black community. Dorsette lost ownership of the building in the 1896 economic depression, however.

Soon after his arrival in Montgomery, Dorsette had married Sarah Hale, but she died after less than a year. Her father was James Hale, the wealthiest black man in Montgomery at that time, and Dorsette convinced him that the city needed an infirmary for blacks. Hale donated land, and a white women's club helped Dorsette raise money for the building and its operation. The first such facility for blacks in Alabama, Hale Infirmary opened in 1890 and operated until 1958.

In 1886, Dorsette married Lula Harper of Augusta, Georgia, with whom he had two daughters. Dorsette had expressed concerns about his health to Washington since the 1890s, and after a damp and cold hunting trip on Thanksgiving Day in 1897, Dorsette contracted pneumonia; he died on December 7. His funeral procession was said to be the largest ever held in Montgomery for a black citizen up to that time. The service was held at what is now Old Ship AME Zion Church, founded in 1852, the oldest black congregation in the city.

Sarah Breedlove

aka Madam CJ Walker

“I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations….I have built my own factory on my own ground.” Madam Walker, July 1912

Orphaned at age seven, she often said, “I got my start by giving myself a start.” She and her older sister, Louvenia, survived by working in the cotton fields of Delta and nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi. At 14, she married Moses McWilliams to escape abuse from her cruel brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.

Her only daughter, Lelia (later known as A’Lelia Walker) was born on June 6, 1885. When her husband died two years later, she moved to St. Louis to join her four brothers who had established themselves as barbers. Working for as little as $1.50 a day, she managed to save enough money to educate her daughter in the city’s public schools. Friendships with other black women who were members of St. Paul A.M.E. Church and the National Association of Colored Women exposed her to a new way of viewing the world.

To promote her products, the new “Madam C.J. Walker” traveled for a year and a half on a dizzying crusade throughout the heavily black South and Southeast, selling her products door to door, demonstrating her scalp treatments in churches and lodges, and devising sales and marketing strategies. In 1908, she temporarily moved her base to Pittsburgh where she opened Lelia College to train Walker “hair culturists.”

By the time she died at her estate, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, she had helped create the role of the 20th Century, self-made American businesswoman; established herself as a pioneer of the modern black hair-care and cosmetics industry; and set standards in the African-American community for corporate and community giving.

Tenacity and perseverance, faith in herself and in God, quality products and “honest business dealings” were the elements and strategies she prescribed for aspiring entrepreneurs who requested the secret to her rags-to-riches ascent. “There is no royal flower-strewn path to success,” she once commented. “And if there is, I have not found it for if I have accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard.”

reprinted from http://www.madamcjwalker.com/bios/madam-c-j-walker/

Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johson

Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson (1864 – 26 April 1901) was an American physician who in 1891 became the first female African-American doctor in Alabama.

Dr. Dillon-Johnson was born Halle Tanner in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the oldest daughter of nine children to Benjamin Tucker and Sarah Elizabeth Tanner. Dr. Dillon-Johnson was well educated and as a young girl became familiar with the work of prominent African-American intellectuals. She worked with her father on The Christian Recorder, a publication of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, where he ministered.

In 1886, she married Charles Dillon and the couple had a child before her husband's sudden death. A widow at 24, she returned to live with her family and decided to enter medical school. After three years of study at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, she earned her M.D. in 1891, graduating with honors.

Around the time of her graduation, African-American educator Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, had written to the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania to request a nomination for a teaching position he had been struggling to fill for four years. He hoped to find an African-American physician to serve the school and its surrounding community. Dr. Johnson accepted Washington's offer of $600 a month, including lodging and meals, and arrived to begin her service in August 1891.

Before beginning her new job, however, the young doctor had to face a significant obstacle: passing the Alabama State Medical Examination. The very fact that she was sitting for the examination caused a public stir in Montgomery, Alabama. She spent ten days taking the exam, addressing a different area of medicine each day. Her examiners included the directors and leading figures of most of the state's major medical institutions. She impressed them with her responses and she passed the test.

During her brief tenure at Tuskegee, she was responsible for the health care of the school's 450 students and 30 faculty and staff. She also established a training school for nurses and founded the Lafayette Dispensary to serve the health care needs of local residents, often mixing medicines herself for their use. She also taught two classes each day.

Dr. Dillon-Johnson's tenure at Tuskegee ended in 1894 when she married the Reverend John Quincy Johnson, an African Methodist Episcopal minister and math instructor at Tuskegee. The couple moved first to Columbia, South Carolina, where Reverend Johnson became president of Allen University, a private school for black students. They later moved from Hartford, Connecticut to Atlanta, Georgia, and then to Princeton, New Jersey, as Reverend Johnson pursued undergraduate and graduate degrees in theology. Finally, in 1900, the couple settled in Nashville, Tennessee with their three children and Reverend Johnson became the pastor of Saint Paul A.M.E. Church. Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson died in Nashville from complications during childbirth.

Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper

Ionia R. Whipper Home for Unwed Mothers

Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper, physician and social reformer, was born September 8, 1872 in Beaufort, South Carolina. She was one of three surviving children born to author and diarist Frances Anne Rollin and Judge William James Whipper.

By 1878, as the Reconstruction period was ending in South Carolina, the Ku Klux Klan, and white supremacist “Rifle Clubs” were gathering forces. Amid an escalating climate of violence, Frances Rollin Whipper took Winifred, Ionia, and Leigh to Washington, D.C. The family established a home on 6th Street NW, and Whipper saw the children through early education and graduation from Howard University. Ionia, after teaching for ten years in the Washington, D.C. public school system, entered Howard Medical School, one of the few schools in the country to accept women.

In 1903, Ionia graduated from Howard University Medical School with a major in Obstetrics, one of four women in her class. That year, she became a resident physician at Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, and on her return to Washington, D.C, set up private practice at 511 Florida Avenue NW, where she accepted only women patients.

In 1921, Dr. Whipper began a tour through the South as an assistant medical officer for the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor. Her mission was to instruct midwives in childbirth procedures. She described in her diary the less than ideal circumstances she encountered there, including prejudice from whites, and suspicion from blacks.

After her tour Dr. Whipper returned to private practice in Washington where she joined the Maternity Ward staff of Freedman’s Hospital. Moved by the plights of numerous unwed teen-agers she assisted there, she began to mentor girls in need. There were no facilities in the area serving black women and girls, and Dr. Whipper began to take individual girls under her wing in her own home and office on Florida Avenue.

Dr. Whipper assisted the girls through their pregnancies and afterwards with infant health care. She soon enlisted seven women friends among her AME St. Luke's Church members and together they began to raise money for a home that would shelter unwed pregnant girls.

By 1931, the group purchased 3 ½ acres in Northeast Washington, D.C. which became the first Ionia R. Whipper Home for Unwed Mothers. Notably for that time, the home was open to all regardless of race or religion. For the next four decades it was the only maternity home for black women in the Washington, D.C. area. The home currently serves at-risk girls between 12 and 21.

Ionia Rollin Whipper spent the last years of her life residing with her family in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. and at the home of her niece, Lelia Frances Whipper in New York City. She died at Harlem Hospital on April 13, 1953.

Dr. Mae Carol Jemison

Mae Carol Jemison (born October 17, 1956) is an American engineer, physician and NASA astronaut. She became the first African American woman to travel in space when she went into orbit aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour on September 12, 1992.

After medical school and a brief general practice, Jemison served in the Peace Corps from 1985 to 1987, when she was selected by NASA to join the astronaut corps. She resigned from NASA in 1993 to found a company researching the application of technology to daily life. She has appeared on television several times, including as an actress in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation. She is a dancer and holds nine honorary doctorates in science, engineering, letters, and the humanities. She is the current principal of the 100 Year Starship organization.

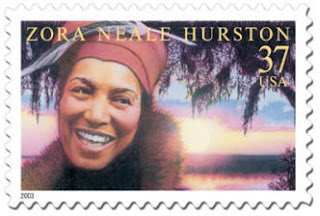

Zora Neale Hurston, Author

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an American novelist, short story writer, folklorist, and anthropologist known for her contributions to African-American literature, her portrayal of racial struggles in the American South, and works documenting her research on Haitian voodoo. Of Hurston's four novels and more than 50 published short stories, plays, and essays, she is best known for her 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama, and moved to Eatonville, Florida, with her family in 1894. Eatonville would become the setting for many of her stories and is now the site of the Zora! Festival, held each year in Hurston's honor. In her early career, Hurston conducted anthropological and ethnographic research while attending Barnard College. While in New York she became a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Her short satires, drawing from the African-American experience and racial division, were published in anthologies such as The New Negro and Fire!!. After moving back to Florida, Hurston published her literary anthropology on African-American folklore in North Florida, Mules and Men (1935) and her first three novels: Jonah's Gourd Vine (1934); Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937); and Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939). Also published during this time was Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (1938), documenting her research on rituals in Jamaica and Haiti.

Hurston's works touched on the African-American experience and her struggles as an African-American woman. Her novels went relatively unrecognized by the literary world for decades, but interest revived after author Alice Walker published "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston" in the March 1975 issue of Ms. Magazine. Hurston's manuscript Every Tongue Got to Confess (2001), a collection of folktales gathered in the 1920s, was published posthumously after being discovered in the Smithsonian archives.

Hurston was the sixth of eight children of John Hurston and Lucy Ann Hurston (née Potts). All of her four grandparents had been born into slavery. Her father was a Baptist preacher and sharecropper, who later became a carpenter, and her mother was a school teacher. She was born in Notasulga, Alabama, on January 7, 1891, where her father grew up and her grandfather was the preacher of a Baptist church.

When she was three, her family moved to Eatonville, Florida; in 1887 it was one of the first all-black towns to be incorporated into the United States. Hurston said she always felt that Eatonville was "home" to her as she grew up there, and sometimes claimed it as her birthplace. Her father later was elected as mayor of the town in 1897 and in 1902 became minister of its largest church, Macedonia Missionary Baptist.

Hurston later used Eatonville as a backdrop in her stories. It was a place where African Americans could live as they desired, independent of white society. In 1901, some northern schoolteachers visited Eatonville and gave Hurston a number of books that opened her mind to literature; she described it as a kind of "birth". Hurston spent the remainder of her childhood in Eatonville, and described the experience of growing up there in her 1928 essay, "How It Feels to Be Colored Me".

In 1904, Hurston's mother died. Her father remarried to Mattie Moge; this was considered a minor scandal, as it was rumored that he had had relations with Moge before his first wife's death. Hurston's father and stepmother sent her away to a Baptist boarding school in Jacksonville, Florida. They eventually stopped paying her tuition and the school expelled her. She later worked as a maid to the lead singer in a traveling Gilbert & Sullivan theatrical company.

In 1917, Hurston began attending Morgan College, the high school division of Morgan State University, a historically black college in Baltimore, Maryland. At this time, apparently to qualify for a free high-school education (as well, perhaps to reflect her literary birth), the 26-year-old Hurston began claiming 1901 as her year of birth. She graduated from the high school of Morgan State University in 1918.

In 1918, Hurston began her studies at Howard University, where she became one of the earliest initiates of Zeta Phi Beta sorority and co-founded The Hilltop, the university's student newspaper. While there, she took courses in Spanish, English, Greek and public speaking and earned an associate degree in 1920. In 1921, she wrote a short story, John Redding Goes to Sea, which qualified her to become a member of Alaine Locke's literary club, The Stylus. Hurston left Howard in 1924 and in 1925 was offered a scholarship by Barnard trustee Annie Nathan Meyer to Barnard College of Columbia University, where she was the college's sole black student. Hurston received her B.A. in anthropology in 1928, when she was 37. While she was at Barnard, she conducted ethnographic research with noted anthropologist Franz Boas of Columbia University. She also worked with Ruth Benedict as well as fellow anthropology student Margaret Mead. After graduating from Barnard, Hurston spent two years as a graduate student in anthropology at Columbia University.[19] Living in Harlem in the 1920s, Hurston befriended the likes of Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, among several others. Her apartment, according to some accounts, was a popular spot for social gatherings. Around this time, Hurston experienced a few early literary successes, including placing in short-story and playwriting contests in Opportunity magazine.

In 1927, Hurston married Herbert Sheen, a jazz musician and a former classmate at Howard who later became a physician. Their marriage ended in 1931. In 1939, while Hurston was working for the WPA, she married Albert Price. The marriage ended after seven months.

She lived in a cottage in Eau Gallie, Florida, twice: once in 1929 and again in 1951. During the 1930s, Hurston was a resident of Westfield, New Jersey, where Langston Hughes was among her neighbors. In 1934 she established a school of dramatic arts "based on pure Negro expression" at Bethune-Cookman University (at the time, Bethune-Cookman College), a historically black college in Daytona Beach, Florida.[23]

In later life, in addition to continuing her literary career, Hurston served on the faculty of North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) in Durham, North Carolina

In 1956 Hurston received the Bethune-Cookman College Award for Education and Human Relations in recognition of her achievements. The English Department at Bethune-Cookman College remains dedicated to preserving her cultural legacy

During the first twenty years of her career, Hurston's work met with great interest. Yet, from the mid fifties until the late seventies Hurston and her work were virtually forgotten, her books were out of print and she appeared as a mere footnote to studies of African American literature. In her later years, Hurston worked at odd jobs to support herself occasionally resorting to public assistance to survive. Among other positions, Hurston worked at the Pan American World Airways Technical Library at Patrick Air Force Base in 1957. She was fired for being "too well-educated" for her job. Her last few years found Hurston working as a maid for a woman who found out about her domestic's literary talents when she recognized her by-line in the Saturday Evening Post.

During a period of financial and medical difficulties, Hurston was forced to enter St. Lucie County Welfare Home, where she suffered a stroke. She died of hypertensive heart disease on January 28, 1960, and was buried at the Garden of Heavenly Rest in Fort Pierce, Florida. Her remains were in an unmarked grave until 1973. Novelist Alice Walker and literary scholar Charlotte D. Hunt found an unmarked grave in the general area where Hurston had been buried, and decided to mark it as hers.

After Hurston died her papers were ordered to be burned. A law officer and friend, Patrick DuVal, passing by the house where she had lived, stopped and put out the fire, thus saving an invaluable collection of literary documents for posterity. The nucleus of this collection was given to the University of Florida libraries in 1961 by Mrs. Marjorie Silver, friend and neighbor of Hurston. Other materials were donated in 1970 and 1971 by Frances Grover, daughter of E. O. Grover, a Rollins College professor and long-time friend of Hurston's. In 1979 Stetson Kennedy of Jacksonville, who knew Hurston through his work with the Federal Writers Project, added additional papers. [(Zora Neale Hurston Papers, University of Florida Smathers Libraries, August 2008)]

While Zora's story may appear to be a sad one to many, I find it to be more of a story of a woman who was curious, inquisitive, highly intelligent, and adventurous but at the same time a woman who fell prey to the limitations of the world in which she found herself.

It's truly a story of a woman who was born in the wrong century.