Avondale was a company town built around the Avondale Mills east of Birmingham, Alabama in Jefferson County. The city was founded in 1887 by the Avondale Land Company which was owned by Benjamin F. roden, William Morris and Martin Sumner. When they purchased the land, the original owner specified that the 40 rugged acres surrounding the spring remain dedicated as a park. The company financed a mule-drawn streetcar line along 1st Avenue North to the proposed business district on 41st Street.The city was annexed into Birmingham in 1910 and is now divided into three separate neighborhoods, North Avondale, East Avondale and South Avondale.

Photo's of intersection of 4th Avenue South and 41st Street in Avondale taken circa 1910

41st Street which dead ends into the Avondale Park circa 2014

The first residents of the area were clustered around "Kings Spring" (named after the original land owner) on the slopes of Red Mountain, now the site of Avondale Park. Once, near the spring, Confederates fired on Union soldiers watering their horses. The wife of Jefferson County sheriff Abner Killough was struck in the breast by a stray shot while sitting on her porch. Her wound is believed to have been the only blood spilled in the county during the war.

The new town, incorporated in 1889, was named after the Cincinnati suburb of Avondale, which impressed the members of the company who had travelled there to seek backing for their development. Cincinnati's Avondale, in turn, was named for "Avondale Parish" in Scotland, the site of the Battle of Drumclog between Covenant and Claverhouse in 1679. The name was used in Sir Walter Scott's "Old Mortality". It is of Celtic origin, meaning "river", and thus several small rivers in Britain are so named, including the one in Warwickshire which flows past Shakespeare's Stratford.

In the 1890 census, 1,000 residents were counted within the borders of the new city. Ten years later that number had tripled, and was closer to 5,000 when it was annexed into Birmingham. Several efforts to secure the annexation of Avondale into Birmingham failed by popular vote.

In 1907 the Alabama Legislature enlarged Birmingham's boundary to include Avondale, Woodlawn, East Lake, several small West End communities, and Ensley. This "Greater Birmingham" annexation became effective on January 1, 1910.

In 1907 the Alabama Legislature enlarged Birmingham's boundary to include Avondale, Woodlawn, East Lake, several small West End communities, and Ensley. This "Greater Birmingham" annexation became effective on January 1, 1910.

Avondale's first mayor, serving from 1887 to 1889 was butcher Henry F. Dusenberry.

Henry F. Dusenberry seated in the center

Miss Fancy

Miss Fancy (born October 12, 1871. Died 1954 in Buffalo, New York) was a large, gentle Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) that served as the star attraction at the Birmingham Zoo, when it was located in the southeast corner of Avondale Park, from 1913 to 1934. Miss Fancy, then 41, was purchased in 1913 from the struggling Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus for $2,000.

The best-documented story is that circus officials had offered her for sale, along with a group of smaller animals, prior their stay in Birmingham; and that a local party, led by Birmingham Age-Herald publisher Ed Barrett, decided to take the opportunity to purchase them as a major enhancement for the animal collection exhibited at Avondale Park since 1911.

Barrett's initial $500 contribution was matched by the Birmingham Railway, Light & Power Company, whose Avondale Streetcar brought visitors to the park. After the circus had moved on, an anonymous donor came through with another $500. His newspaper solicited contributions "to pay the remaining debt on 'Miss Fancy', and printed donors names, divided into "children" and "grown-ups". By January 1914 the "Miss Fancy Fund" stood at $129.25. The fund eventually raised the remaining $500 to pay the debt.

There are other accounts of Miss Fancy's purchase. A more prosaic version has a city zoo official approaching the struggling circus during its stop in Birmingham. Another story has it that the Birmingham Advertising Club obtained her for a promotional gimmick, then offered her to the city once the novelty faded. A more colorful version, promulgated by former Miami Herald editor Ellis Hollums, was that Barrett won the elephant from the circus owner in a poker game.

Barrett's paper presented the animal as a gift "to the children of Birmingham" (though the city never recorded her as public property). In some versions, the $500 raised by schoolchildren went into a fund to provide for Miss Fancy's care.

In the summer of 1914, the city budgeted $500 for a green-painted elephant house at the Avondale Park zoo, and $1,872 for the zoo's overall operational expenses for the year.

Miss Fancy was initially placed under the custodianship of Dayton Allen, assisted by John Todd, an African American zoo worker. The two of them were instructed on her care and handling by circus trainer Curly Hayes, who warned that the elephant had killed one man and injured another.

Allen resigned not long afterward, giving Todd full-time charge of Miss Fancy at a wage that peaked at $24 per week. He remained her handler for the remainder of her tenure in Birmingham. Todd used an elephant hook in her training, taking care "never to use the hook unless she has done wrong, and knows that she has done wrong."

Early on, Todd had to leave the zoo for ten month's service in World War I. Despite the efforts of keeper Luell Williams, Miss Fancy "wasted away" to a fraction of her 4,800 pounds while Todd was gone. Upon his return, she greeted her master cheerfully with a series of trumpet blasts. Thereafter Todd's vacation weeks were invariably interrupted by a request that he come back and spend some time with his elephant to calm her down.

Allen resigned not long afterward, giving Todd full-time charge of Miss Fancy at a wage that peaked at $24 per week. He remained her handler for the remainder of her tenure in Birmingham. Todd used an elephant hook in her training, taking care "never to use the hook unless she has done wrong, and knows that she has done wrong."

Early on, Todd had to leave the zoo for ten month's service in World War I. Despite the efforts of keeper Luell Williams, Miss Fancy "wasted away" to a fraction of her 4,800 pounds while Todd was gone. Upon his return, she greeted her master cheerfully with a series of trumpet blasts. Thereafter Todd's vacation weeks were invariably interrupted by a request that he come back and spend some time with his elephant to calm her down.

Miss Fancy was an early and enduring favorite of the city's schoolchildren. She was known to recognize visitors who brought her treats and gave them special attention whenever they were in sight. Todd would often help as many as six or seven young children onto her back for a ride around her pen. Though many parents initially balked at the thought, the gentle elephant gradually earned the trust of nearly every parent.

The opportunity was not given to all, though. African-Americans were not admitted to Avondale Park under the city's segregation laws. The publicity surrounding the new attraction led members of the 16th Street Baptist Church to petition the city to be allowed to picnic at the park one Sunday. The Birmingham City Commission accepted the petition, and decided to allow all Black residents to visit the park on July 9, 1914. The decision was harshly criticized by the Avondale Civic League however, and the church withdrew its request.

The opportunity was not given to all, though. African-Americans were not admitted to Avondale Park under the city's segregation laws. The publicity surrounding the new attraction led members of the 16th Street Baptist Church to petition the city to be allowed to picnic at the park one Sunday. The Birmingham City Commission accepted the petition, and decided to allow all Black residents to visit the park on July 9, 1914. The decision was harshly criticized by the Avondale Civic League however, and the church withdrew its request.

Miss Fancy was a feature of almost any parade organized in the city. She was considered an informal mascot for Howard College (Now Samford University), and at least once was permitted to lead the college students on their parade all the way to Legion Field for the Bulldogs football game against Birmingham Southern College.

Over the next two decades, Miss Fancy's weight climbed to 8,560 pounds. She was reported to have eaten 125-170 pounds of hay, and three to five gallons of grain per day, washed down with 50-110 gallons of fresh water (depending on the weather), all supplemented by popcorn, peanuts, apples and watermelons brought to her by residents. In 1931 her food was reported to cost the city about $100 per month at wholesale prices, about 40% of the total monthly grocery bill for the zoo. Contemporary sources reported that elephants were expected to live to 350 or 400 years, and her keepers believed that she was in the bloom of youth and should be growing steadily to maturity at about age 75. It is now estimated that Asian elephants live an average of 60-80 years.

Miss Fancy was exercised daily by giving rides to children and chauffeuring Todd on 5 to 10-mile excursions through nearby neighborhoods. She also helped the occasional stuck motorist out of a pothole. Well-trained with "Short Indian" commands in from her circus days, she would perform a number of tricks, but only for Todd.

Miss Fancy was also known to be a medicinal drinker. Whenever she showed symptoms of chills or constipation, a dose of "elephant medicine" was, on the advice of a veterinarian, mixed with a quart of liquor and diluted with a few gallons of water.

Since her time in Birmingham coincided with statewide prohibition, city officials provided her with confiscated whiskey. Some of the "Shelby corn" was rumored to have found its way into Todd's throat, too. Some say he was routinely seen in an inebriated state, but only one specific incident made the newspapers.

One afternoon in early 1934, Todd was under the influence when he clambered onto Miss Fancy's back for a ride up the hill. A resident noted their behavior and summoned the police. They made an unsuccessful attempt to arrest Todd, but were discouraged by the elephant's protests. The best they could manage was to send the pair on their way back to the zoo to sleep it off.

Since her time in Birmingham coincided with statewide prohibition, city officials provided her with confiscated whiskey. Some of the "Shelby corn" was rumored to have found its way into Todd's throat, too. Some say he was routinely seen in an inebriated state, but only one specific incident made the newspapers.

One afternoon in early 1934, Todd was under the influence when he clambered onto Miss Fancy's back for a ride up the hill. A resident noted their behavior and summoned the police. They made an unsuccessful attempt to arrest Todd, but were discouraged by the elephant's protests. The best they could manage was to send the pair on their way back to the zoo to sleep it off.

Miss Fancy outgrew the elephant house constructed for her and had to drop to her knees to pass under the door. Nevertheless, she spent most of the winter indoors, heated by a small stove. Her outdoor pen was enclosed by an iron railing during the day. She was sometimes permitted to graze on the mountainside. Todd also saw to Miss Fancy's regular grooming.

She was treated to a cooling shower every other day during the summer and given the full soap-and-water scrub, followed by a brushing of five gallons of neatsfoot oil twice a year — on her birthday in October and again in Spring. Her toenails were rasped smooth at those times, and her tusks were cut back to nubs every couple of years to limit the amount of damage she could do on the loose.

She was treated to a cooling shower every other day during the summer and given the full soap-and-water scrub, followed by a brushing of five gallons of neatsfoot oil twice a year — on her birthday in October and again in Spring. Her toenails were rasped smooth at those times, and her tusks were cut back to nubs every couple of years to limit the amount of damage she could do on the loose.

Twice a year she would suffer a "period of madness" that lasted about 48 hours, during which Todd remained nearby and she was restrained by leg irons at night. On at least twelve occasions she broke loose from containment and wandered the streets of Avondale, Woodlawn and Forest Park, sampling the delights of kitchen gardens and peeping into windows.

She was almost always a gentle presence, easily coaxed back to the park with the lure of food. On at least two occasions, though, she caused damage to property. Once, in 1925 she knocked over the park's cookhouse and kicked over a couple of water hydrants before heading up the hill. Todd caught up with her in Mountain Terrace and coaxed her back to the zoo. Repairs cast the city $75. In Spring of 1931 she bolted from her grazing area and barreled through the trees up Red Mountain until she was caught on Overlook Road.

She was almost always a gentle presence, easily coaxed back to the park with the lure of food. On at least two occasions, though, she caused damage to property. Once, in 1925 she knocked over the park's cookhouse and kicked over a couple of water hydrants before heading up the hill. Todd caught up with her in Mountain Terrace and coaxed her back to the zoo. Repairs cast the city $75. In Spring of 1931 she bolted from her grazing area and barreled through the trees up Red Mountain until she was caught on Overlook Road.

The $4,600 annual expense of keeping the animal menagerie operating led the Park Board to suggest closing the zoo as early as 1932. The Birmingham Board of Education declined an offer to take over Miss Fancy's care, as did former Mayor George Ward, proprietor of the Roman-styled Vestavia estate on Shades Mountain. He told the board that "Lions, tigers and elephants contributed to the downfall of the Roman Empire. No elephant will have the opportunity to bring about the disintegration of my Roman empire."

Miss Fancy was ultimately sold, along with the rest of the park's exotic animals, to the Cole Brothers - Clyde Beatty Circus of Rochester, Indiana for a total of $710. Circus crews arrived on November 11, 1934 to accompany the elephant to her new quarters in Peru, Indiana. The first boxcar proved too small for the giantess, and she waited by the rail siding for a larger carriage, which departed the city about 7:00 PM. Todd rode with her, but soon returned to Birmingham and worked in the city's greenhouse.

The Cole Brothers soon announced the acquisition of "Frieda", an 8,600 lb. elephant from Birmingham, "which towered over the other three in the elephant row". That name didn't seem to stick, and she toured with the circus as "Bama" in 1935 and 1937.

The Cole Brothers soon announced the acquisition of "Frieda", an 8,600 lb. elephant from Birmingham, "which towered over the other three in the elephant row". That name didn't seem to stick, and she toured with the circus as "Bama" in 1935 and 1937.

In April 1939 the circus sold her to the Buffalo, New York zoo, which had been newly expanded with help from the Works Progress Administration. She remained there until her death in 1954.

Miss Fancy was fondly remembered by the children that had seen her at Avondale Park, and featured in stories passed down from generation to generation of her excursions around the surrounding neighborhoods and of her notorious drinking habits. She was also mentioned in Fannie Flagg's novel "Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe".

For more information or to donate to this cause, please visit http://queenofavondale.com./

Miss Fancy's image was adopted in the logo of the Avondale Brewing Company and features in the brewery's decor and in the names of products such as "Miss Fancy's Tripel" and "Vanillaphant Porter". She also lent her name to Fancy's on 5th, an oyster bar located across 5th Avenue from the park.

Avondale Park

Avondale Park, a 40-acre preserve on the slopes of Red Mountain, enshrined the natural spring and was, for a while, the largest park in Birmingham. Other features included a wading pool, a pavilion, ballfields, the Villa and an early version of what would become the Birmingham Zoo, featuring Miss Fancy the well-loved elephant.

The Park was the largest in Birmingham until Ruffner Mountain Park was dedicated. It was known for the spring-fed grotto pool, an extensive rose garden, athletic fields, a secluded pavilion called "The Villa", and a large amphitheater that hosted a spectacular pageant in celebration of Birmingham's 50th anniversary in 1931. The park was also one-time home of the Birmingham Zoo, which at the time consisted mainly of non-exotic species with the exception of "Miss Fancy".

A natural spring, called "Big Spring," in what is now Avondale Park was already known to stagecoach travelers in the mid 19th century. Proclaimed as the sweetest waters in the region, It was conveniently located near the junction of Georgia Road and Huntsville Road (present day 5th Avenue South and 41st Street). It was part of a large land grant given to two-time Jefferson County Sheriff Abner Killough.

Killough sold the area around the spring to Peyton King, who built his home right alongside it. For a long time the location became known as "King Spring", and was a popular picnic destination for the pioneer residents of Birmingham. In 1872 the Alabama Great Southern Railway extended along the valley a few hundred yards north of the spring. A large railyard with shops and a roundhouse were built around the present 35th Street and provided significant employment in the area until they were superseded by the Finley Yards in the 1910s. Within a few years the Great Southern was joined by the Seaboard Air Line Railway and the Georgia Central Railway. Seaboard built a roundhouse and yards in Avondale.

The spring emerged from a cave, now sealed off and proceeded to flow through the center of Spring Street (now 41st Street), the primary commercial center of Avondale.

After many years of decline, the park has since seen a rebirth. In 2011, the city of Birmingham undertook a $2.88 million restoration of the park. In 2013, The Forest Park South Avondale Business Association sponsored the installation of free WiFi throughout the park.

Rose garden at Avondale Park

Movie night at the Avondale Park Amphitheater

Avondale Villa at Avondale Park

Avondale Villa at Avondale Park

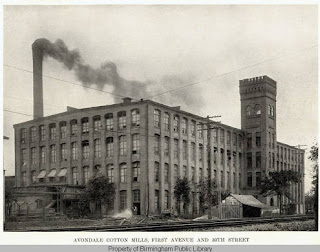

Avondale Mills

Avondale Mills was built just outside the limits of the town in 1897 and became one if the area's largest employers. Important manufacturer's in Avondale included the Smith Gin Company (later merged into the Continental Gin Company, and the Avondale Stove and Foundry Company.

As Avondale's commercial district grew, the Spring Branch, which was the spring's outlet, flowing north, adopted two open channels on either side of the street. Movements to improve the street by paving over the stream were frequently discussed, but it was not until Labor Day of 1925 that the street was finally paved and the stream conducted through a storm sewer in the center of the right-of-way.

From its founding in 1897, textile manufacturing firm Avondale Mills left its mark on towns and cities throughout Alabama. Avondale Mills earned the respect of many mill workers for its progressive programs for employees, and the disdain of reformers for its labor practices, particularly the use of child labor. Avondale Mills spanned the rise and fall of Alabama's industrial history, and its most notable owners, the Comer family, became some of the most powerful people in the state. The company ceased operations in July 2006, unable to compete with foreign textile manufacturers and unable to recover from a tragic train accident next to its Graniteville, South Carolina, facility in 2005.

In 1897, Comer built the first mill in the Birmingham neighborhood of Avondale, hence the name Avondale Mills. By 1898, Avondale Mills employed more than 400 people as spinners, weavers, and mechanics and generated $15,000 in profit. In 1906, B. B. Comer was elected Governor of Alabama but remained president of the company, although he turned over its management to his son James McDonald (Donald) Comer. The following year, Avondale Mills declared $55,000 in profit and produced almost 8 million yards of material.

Avondale drew large numbers of poor Alabamians who were looking for work. For many former sharecroppers and tenant farmers, both black and white, the steady paychecks and working hours were very appealing compared with life on the farm at a time when cotton prices were falling. A farm laborer who had been earning a potential $400.00 annually could work in a textile mill for a potential $700.00 annually. And with other family members working in the mill, family income rose accordingly.

Avondale Mills School

Employee housing for Avondale Mills

Avondale School

Lunch Counter at Avondale Mills

Avondale Street Car

Comer's relationship to labor never progressed past his strong plantation-paternalism, an attempt to control almost every aspect of the mill worker's life. He controlled their working conditions at the mill, and by providing housing, recreation, and places of worship, he controlled some of their private lives. One of Comer's first initiatives was to provide a place of respite for all of his workers. He purchased land near Panama City, Florida, and created a beach-front park where members of the Comer family and Avondale workers could swim, boat, and fish. Later named Camp Helen, the park had a large central building with a number of scattered guest cottages. Camp Helen is now a Florida State Park.

The mills closed at different times during the summer to allow employees to visit the camp. African American workers were also allowed separate time to use the facilities.

Despite the amenities B. B. Comer provided to his workforce, he and the company have been criticized for their extensive use of child labor in the mills and for opposing legislation to restrict such labor. One historian documented 187 children (out of 774 employees) ages 8 to 15 working in the Birmingham mill in 1900. Some families reluctantly allowed their children to be employed at the mill, but other families, which were accustomed to all members laboring on the farm, often welcomed the opportunity for their children to work and earn a paycheck. Comer claimed that families demanded their children have the opportunity to work; hence he simply responded to the will of his employees. Labor reformers noted that there were important differences between farm work and factory work. On the farm, children worked hard but at their own pace with no penalty for stopping. The relentless pace of the mill, however, endangered children because they often did not have the stamina or physical strength to work long hours. A misstep around a running machine was much more dangerous than getting tired in an open field. Also, even when children were employed to sweep the floors, a fairly safe activity, they were absent from school.

When Donald Comer took over, he began to reevaluate Avondale's relationship with its work force and expanded on his father's progressivism. Historians have noted that Donald had a more personal relationship with his employees and interest in their lives. He introduced a profit-sharing plan wherein profits were split between the company and employees. Each month, the employees received a check based on the profits from the previous 12 months. Donald Comer also prided himself on offering the same opportunities to African Americans at a time when racism was pervasive and institutionalized throughout the South; of the 8,500 people Avondale employed in 1947, 12 percent, or about 1,020 individuals, were African American.

Workers housing

Known to mill workers as "Boss," Donald Comer earned the appreciation of many workers, who were known as operatives, and his efforts generated a sense of pride in the Avondale Mills communities. Bragg Comer, another of B. B. Comer's sons, supervised the construction of Drummond Fraser Hospital, a 35-bed hospital for Avondale workers. At one point, Avondale even provided a canning plant, though employees had to pay for the cans. Avondale Mills also owned Camp Brownie on the Coosa River, which offered boating opportunities for employees and their families.

In its 109-year history, Avondale Mills expanded to include plants throughout Alabama. By the years 1947 and 1948, Avondale Mills had reached its apex with 7,000 employees. The plant's production efforts consumed 20 percent of Alabama's cotton crop. In 1951, Comer released control of Avondale Mills to James Craig Smith Jr. Later, Avondale branched out into Georgia and South Carolina.

In 1986, Walton Monroe Mills Inc. purchased Avondale Mills. The two companies operated separately but shared a board of directors. In 1993, the two merged to become Avondale Incorporated. Avondale Mills Inc. became a subsidiary of Avondale Incorporated. Three years later, Avondale acquired the textile assets of the Graniteville Company. Twelve years later, at Graniteville, in the early morning of January 6, 2005, a Norfolk Southern train went through a misaligned track switch at 50 miles per hour. The train hit a parked locomotive and launched 16 cars, including a tank car with 90 tons of chlorine, into a lot adjacent to Avondale Inc.'s data processing center. The tank ruptured and sent a vapor cloud through Graniteville and the mill. Five Avondale workers were killed and the chlorine gas destroyed computers and equipment. Avondale released 350 employees from the Graniteville facility.

Repercussions of the train wreck rippled throughout Avondale Mills until in July 2006, Avondale Incorporated ceased operations and sold three of its plants to Parkdale Mills Inc. Avondale closed three plants in Sylacauga and one plant each in Alexander City, Pell City, and Rockford, laying off more than 1,300 workers. The purchase by Parkdale Mills saved jobs in Alexander City and Rockford, but in January 2008, Parkdale closed its plant in Rockford. Overall, more than 4,000 workers in several states lost their jobs when Avondale shut down. Many of the workers affected by the layoffs have been eligible for federal job training and reemployment assistance. On June 22, 2011, the Avondale Mills Eva Jane plant building in Sylacauga caught fire and burned to the ground.

Sloss Furnace

Sloss Furnaces, a Birmingham based iron manufacturing complex, was established in 1881. The furnace and its various owners played a large role in the economic development of Birmingham. The site was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1981, one of the few industrial sites to be so designated, and offers visitors a chance to experience Birmingham's industrial history. It is now an educational museum and home to a community of metal-working artists.

Colonel James Withers Sloss, a plantation owner and railroad developer from Athens, Alabama, founded the Sloss Furnace Company in the midst of an industrial boom that grew from Birmingham's unique proximity to large deposits of coal, iron ore, and limestone in or near the Jones Valley.

Colonel James Withers Sloss

Sloss built two blast furnaces that went into production in April 1882 and May 1883, respectively. The furnaces, which featured a modern heated air-blast system, were located at the confluence of the Louisville & Nashville (L&N) and Alabama Great Southern railroads on the east side of the city.

Joseph Bryan, a young attorney, led the Virginia syndicate and played a strong role in Birmingham's development for more than two decades. The son of a wealthy tobacco planter, he was rooted in the upper classes of the antebellum plantation-agriculture system and had strong ties with northern bankers active in financing the shipment of southern agricultural commodities to Europe.

Bryan and his fellow Virginians, mostly veterans of the Confederacy, were attracted to the postwar South because they believed that labor costs would be low, given the region's large pool of African Americans seeking to escape the exploitation of sharecropping. This outlook permeated the future development of Sloss Furnaces. The Virginia industrialists also took advantage of the convict lease system which allowed them to lease prisoners at little cost to work in mines and other dangerous jobs. Sloss employed large numbers of convicts in its mines, including the Coalburg mine, which was known for its deplorable conditions and for its high death rate. In 1890, 90 of 1,000 prisoners died in the mines. Indeed Sloss continued using convict labor after other large companies ended the practice.

Bryan and his associates developed a satellite community, North Birmingham, where they built two additional blast furnaces and, in addition to Coalburg, established an increasing number of mining camps and company towns, including Blossburg, Brookside, and Cardiff, which was named for the predominantly Welsh immigrant workers who lived at the camp.

Sloss and another local firm, the Woodward Iron Company, founded in Anniston, became America's two main producers of foundry pig iron. Paradoxically, the Sloss Iron and Steel Company and the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company never made a single ounce of steel.

During the 1970s, increasing environmental regulations and energy shortages drove production prices to the breaking point, forcing the company to shutter its Alabama factories in 1980. The new blast furnace was torn down after being put out of operation, but the 1920 plant designed by Dovel was saved after a group of concerned citizens lobbied for its preservation. It was designated as Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in September 1983, with the help of a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Lake at Sloss Furnaces

View of Sloss Furnace from the air

View of Sloss furnace from 1st Avenue North

About two-thirds of the historic structures on the site were stabilized using the bond funds approved by Birmingham voters in 1977. Parts of the site were also adapted for use as a center for community and civic events and for an innovative program in metal arts. Sloss now hosts concerts, festivals, and conferences, as well as workshops and exhibitions of metal art. By helping people form new attachments to the old furnaces, these programs keep Sloss an active and important part of the community, as it was for almost a hundred years.

Sloss is currently the only twentieth-century blast furnace in the U.S. being preserved and interpreted as an historic industrial site. The dramatic scale and complexity of the plant’s industrial structure, machines and tools make the Sloss collection a unique contribution to the interpretation of twentieth-century ironmaking technology and presents a remarkable perspective on the era when America grew to world industrial dominance. At the same time, Sloss is an important reminder of the hopes and struggles of the people who worked in the industries that made some men wealthy, and Birmingham the “Magic City.

ReplyDeletehello Dr Obodo,its really amazing to know that in this world we have people like u who are able to come up with excellent ideas or tactics to help people are hurting to win back their love.I am so grateful to tell u that i have my girlfriend back.Thanks for all the wonderful tactics that has been useful to me. Dr Obodo,U ARE WONDERFUL & I APPRECIATE IT. For those who need help ( templeofanswer@hotmail.co.uk )